OUT OF A NIGHTMARE, NEW GROWTH

Fortunately for the Grand Canyon — the Greater Grand Canyon— fortunately I insist, the Hualapai’s next big effort, allied with Hayden (and a bunch of Western politicos) their next effort did not bring victory. This effort, did, however, act as a huge hinge in history: of the Canyon, its overall region, the American west, and society at large. That hinge was, of course, the monumental struggle over whether to authorize and build two hydroelectric dams in the Grand Canyon, a move that would have continued, ratified, indeed intensified, 20th-century over-development of the West, and turned the Greater Grand Canyon into the Grand Canyon National Industrial Park.

This is not the place to re-narrate that struggle; the dreamers of dams were defeated; the dams were not authorized. America chose instead to “Save Grand Canyon” and possibly itself as marked by the consequent burgeoning of our environmental consciousness. The outcome of this larger effort, comprehending and dealing with the consequences (e.g., negative climate alteration and weather unpredictability) of this Anthropocene age of ours, is yet to be known. The story of the Greater Grand Canyon is only one, if a singularly significant one, strand of the many that humans are weaving to make our future, for better and worse.

In 1966, for us advocates of a dam-free Grand Canyon, it was battle-time, and the banner we chose to fight under was:

No to any dams.

Yes to a complete Grand Canyon National Park.

Fifteen years earlier, there had been a similar struggle over building a dam in Dinosaur National Monument. Defined as a save-our-Park-System effort, it was successful. Yet, the narrow definition of the matter at issue, left out other stretches of the Colorado River landscape; most importantly, most tragically, Glen Canyon, that loveliest sculptured place only a few (not me, sob) were ever able to see free and clear. The damming and drowning of Glen Canyon delivered a world-view-altering change in how defenders of the scenic masterpiece called the American West set their goals. No more, just save the Parks; now it was “save the place”: “Save Grand Canyon”, all 277 miles, from damming.

The significance of 1966 is two-fold: it saw the best effort of the would-be dammers, and they failed. It saw the birth of a continuing effort to create a complete National Park, the effort marked and celebrated in the proclamation 57 years later of Baaj Nwaavjo I’tah Kukveni National Monument.

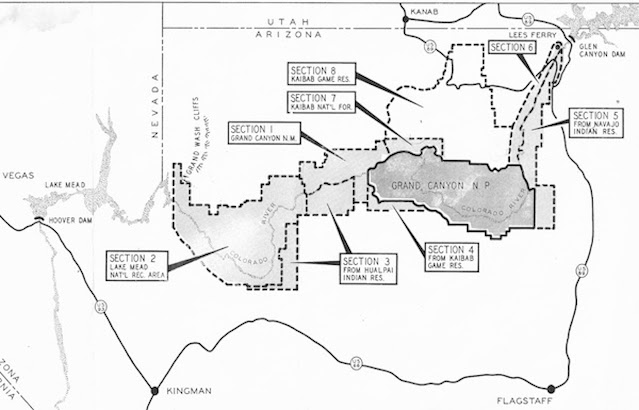

O.K. Mea culpa, mea culpa. When in March 1966, Martin Litton and I were set to work by David Brower (Executive Director of the Sierra Club, a leader of the anti-dam forces) to come up with a positive statement, above and beyond “No to dams”, we drafted a congressional bill for a COMPLETE PARK that included lands that did not belong to us white folks, namely, in the Hualapai and Navajo Reservations. Here is that creation: It is worse than it appears.

Section 2, Lake Mead, actually includes the swath, the northern third, of the Hualapai Reservation south of the Colorado. The Havasupai are not even noted, and lands they hoped to have restored to their jurisdiction were marked for the Park. The Navajo portion includes taking away Marble Canyon and beyond. Interestingly, the loudest howls came from Arizona hunters, who saw including portions of the Kaibab Game Reserve as poaching on their sacred ground.

Bills including this aggrandizing Park were introduced in the House of Representatives, and amid a fury of opposition and scorn, sank, lessons for us newbies to Grand Canyon politics on the limits of what we might even just conceive. So, take this as a historical footnote: Baaj Nwaavjo I’tah Kukveni N.M., in its own conception by the Associated Tribes lands and rights, propounds a Greater Grand Canyon of more extensive inclusiveness (but not shifts of ownership) than even that “complete” National Park of 1966.

Fast on our drafting feet, we drew up a new map and proposal for (as) complete (as it can be) Grand Canyon National Park. We drew up this more modest attempt with no Reservation lands, and grounded desirable additions as delineating the 277 miles of the Colorado mainstem and lands that were its local drainage, that is, most of the side canyons and chunks of the plateaus they were dug into. Here’s my sketch from 1967:

And by 1969, cleaned up into the following map (our upside-down turkey), we had found a sponsor, the admirable Republican from New Jersey, Senator Clifford Case, who was very fond of the Priestley quote about "every federal official should be proud to be on the staff of the Grand Canyon" (from Midnight on the Desert).

We now included only the west side of Marble Canyon (later we dropped the Paria, leaving only its junction; Paria river had a different future), the mainstem, lower Kanab and Cataract-Havasu Canyons (pace Havasupai, your time approaches), the Whitmore-Parashant Esplanade and canyons, the Kanab and Shivwits Plateaus, and the strange little wattle at the end, about which more elsewhere.

With the dam fight done, this was to shape our offering in the coming congressional effort to protect and enlarge Grand Canyon National Park. However, the door swinging on this great 1966 hinge opened on far more than a Park.

No comments:

Post a Comment