With the closing of the 89th Congress (1965-6), a tumultuous period in the political history of the Grand Canyon also ended. The massive, desperate effort to construct kitchen-sink legislation that would satisfy all the Colorado Basin states foundered in the House of Representatives, in some part because of Californian anxieties aroused by uncertainties as national opposition to the dams grew. The main signal that the party had moved on, however, came after Congress closed, as Interior Secretary Udall ordered Reclamation to study dozens of alternatives to the dams. But the alternatives were limited: No longer were they to be grand cash cows to provide for bringing new water to Los Angeles; the Secretary only wanted ways to pump water to Central Arizona while maintaining the water project's financial feasibility.

This is a moment to remember what may be the keystone to the dams' demise, though failure here has many fathers. In my entries about the 1940's-50's history of the dams, I pointed out that they had become inextricably tied to the Central Arizona water diversion as a Reclamation project (called for many years the Bridge Canyon project), subject to Reclamation laws. As time went on, it was clear that the consequence of this connection was that the dams would never be authorized purely as hydroelectric generators. Their fate would always be bundled up in the complications of Reclamation law and the Western water politics it was part of. Then, once the federal proposal was advanced that their cash might be used to suck water from the Pacific Northwest in the grandest of Reclamation schemes, the dams were doomed, since it became clear that the Arizona water project did not need them. Reclamation, ironically, proved this by coming up with some thirty schemes to pump and pay for Arizona's water.

The scheme chosen, using federal funds to invest in a proposed coal-fired powerplant as a kind of pre-payment to pump the water, was modest and clever. It distresses some to think about that situation, since they have the false impression that Grand Canyon advocates proposed and were in favor of the mining and burning and smoking of coal that powers the Navajo generators at Page. We did not and were not. We wanted to protect the Canyon; Arizona wanted its water. The politicians, as is their responsibility, found a way to satisfy both demands. And as the administration and its Senatorial allies crafted the bill to handle those demands, new initiatives for enlarging the Park emerged.

PARK PROPOSALS, 90TH CONGRESS, A CATALOG

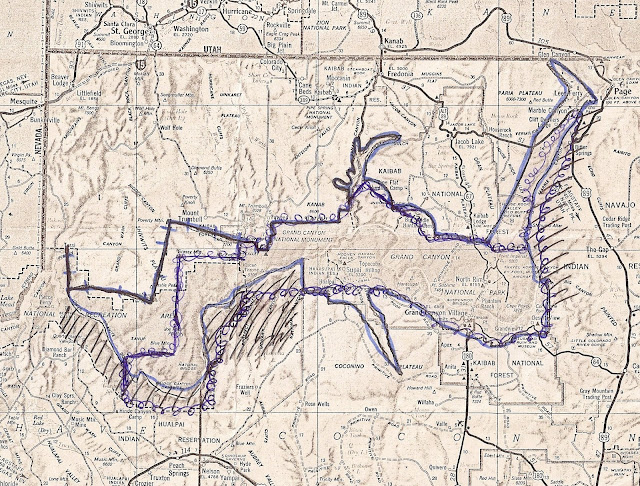

A Park bill was not going anywhere in 1967, but various points could be made laying down claims for the future, or just to score off an opponent. To sort them out, we need a guide map; this one shows the Park boundary in a bill introduced by Senator Case:

The numbers & letters refer to choices about what to include or delete from the Park:

1 Where to start an expanded Park? Everyone wanted to go upstream to include Marble, but how far? L means to Lees Ferry, B where the highway bridge crosses some 4 miles downstream.

2. How much of each side of Marble Canyon would be included? The letters will distinguish between the different ideas for the west side (federal land) and the east (Navajo).

3. Should Navajo land be taken to add the Little Colorado River canyon?

4. NPS wanted the small Coconino or Papago addition for administration.

Note that since NPS was drawing the maps, it could include fixes it had settled on in the 1950's.

5. NPS had blown hot and cold over adding Long Mesa. It was just west of the Havasupai Reservation of the time.

6. The Park boundary here cut straight across two pieces of the rim. The idea was to swap the two tips so that below the rim was in the Park.

7. This piece of the forested land in the Park was wanted by the hunters.

8. The lower Kanab addition was desired by the Park; one of its 1950's fixes; Park advocates wanted to take in even more of the Kanab canyonlands.

9. There were four pieces of plateau in the Monument that grazers and hunters had long wanted and that NPS had been willing to give up.

10. The offset 10 indicates the pro-dam idea of taking the western Park and the Monument and degrading their status to a recreation area so as not to block Bridge Canyon dam.

11. The legal-line extension downstream went to the Bridge Canyon damsite in order to block that dam.

12. This more ambitious extension took in the Lower Granite Gorge down to the west line of the Hualapai Reservation.

Here are the proposals that the Canyon's friends and foes came up with as 1967 went on:

1. Representative Saylor was first. He had struck out on his own, introducing on 10 Jan 1967 HR 1305, using map LNPSW-1000-GC.* The bill itself was much simpler than our proposal he had introduced in 1966 as HR 14176. Section 1 named the map. Sections 2, 3, & 4 required Hualapai & Navajo approval if their lands were to be included in the Park; they were still to be compensated for any activity they must "curtail to meet the standards of national park administration". Section 6 repealed the provision for allowing reclamation projects in the Park, and 7 removed Federal Power Commission authority to license a dam, while vacating all water and power withdrawals.

His boundary went upstream to 1B to block Marble Canyon Dam and downstream to 11 to block Bridge. He ignored the major plateau deletions (9). His eastern boundary included 2E to the rim as well as the Little Colorado (3). He adopted the NPS fixes of 4, 5, 6, & 8. In July, he revised his proposal (map LNPSW-1007-GC) slightly to go up to Lees Ferry, 1L.

2. Although the administration and the Senate were in line to go for a dam-less, more modest, water project bill, the House Interior Committee, led by Coloradan Aspinall and Arizonan Morris Udall, remained on the more grandiose tack of authorizing the bigger, downstream dam. To emphasize this, Aspinall, along with his Senate colleagues Allott & Dominick, introduced HR 6132 (S 1243) on 27 February. With their left hands, they eliminated the Monument and the Park west of Kanab (10), thus "legally" clearing the way for Bridge Canyon dam. With their generous right hands, they added both sides of Marble Canyon (2E & W) up to 1B, plus some of the Vermilion Cliffs.

In this pro-dam anti-Park bill, they included the phrase "The Grand Canyon National Monument is hereby abolished." It was such a stunning evocation of the threat posed to the Canyon and the Park System that we used it as the headline of one of our full-page newspaper ads.

3. The administration was working on countering Aspinall's counter-move, trying to settle on what could be agreed upon between Interior and Agriculture. A Secretarial exchange of letters (27 Feb and 2 Mar) settled on Kanab, Marble, & Coconino: 2, 4, & 8. Determined not to antagonize the Navajo in drawing up legislation, in February NPS Director Hartzog directed local NPS officials to talk with Navajo leaders about GCNP expansion. A meeting with the Navajo Natural Resource Director to discuss Saylor's inclusion of Marble east (2E) and the Little Colorado (3) brought a resounding NO. Shorn of any Navajo land, Interior had their draft to Congress by 9 March. Interior-NPS strategy was not to stir up Navajo antagonism, but to work toward long-range establishment of ties. An NPS fly-over of Marble confirmed the feeling that Marble was a striking feature that should be protected for river running, but maybe Park status was not needed for the entire reach or the east side. Thus, of these new proposals, pro and anti Park, the administration bill was alone in limiting itself to Marble's west side.

On 13 March this bill was introduced in the Senate by Interior Committee Chairman Jackson (of Washington, thus a key figure in the Pacific Northwest's defense of its water). S 1300, map LNPSW-1004-GC, added Marble Canyon (only 2W, taking no Navajo land) up to 1L, plus NPS fixes 4, 6, & 8. It left the Monument and rest of the western Canyon as is. None of the deletions (9) were included; nor anything downstream. In April, the Secretary's Parks Advisory Board commended him on finding an alternative to the dams, and suggested complete protection of the Canyon would mean an extension west to take in the Monument, as well as Marble (2W) and the NPS fixes of 4,6, & 8.

4. Then, just as the Senate Committee took up the water legislation in May, a new, unexpected, voice played a trump. Senator Clifford Case of New Jersey, on his own initiative, introduced S 1686 on 5 May. His map LNPSW-1006-GC (see above) extended the Saylor enlargement upstream to 1L and downstream to 12, but using a natural feature, the Lower Granite Gorge rim, instead of township lines. Otherwise his line matched Saylor's. My guess is that he had NPS advice in its greater extensions, but no matter; we enthusiastically welcomed his initiative.

5. Less welcome was an offering put forward 14 Apr by the Arizona hunter group, the AGPA, which advocated removing all of the land above the rim from the north side of the Monument and the western chunk (Quaking Asp area) of the Kaibab forest (deletions 7 and the 9's), while adding the NPS fixes 4, 5, 6 , & 8. They thought the lower Kanab addition had scenic and geologic significance. They were ok with a Marble rim boundary, but opposed anything that would affect the buffalo ranch, as Aspinall's bill did. They could not see the point of his Vermilion Cliffs addition, either. From our point of view, this was anti-Park, but by emphasizing the rim as the boundary, the AGPA adopted the compromising sensibility of give-some-get-some.

6. Speaking as home folks, the Arizona chapter of the Sierra Club offered its own ideas after consulting with hunters. See below for discussion.

7.The next year, by the way, Congressman Sam Steiger introduced a pro-Havasupai repatriation bill on 30 Jul 1968. His HR 19072 belonged in a different debate, focussing on Havasupai grazing by transferring plateau land from both the Park and the Forest. Although going nowhere at this time, it was a trumpet call we might well have attended to had we not been otherwise absorbed. Interestingly, Steiger's proposal was very close to the reservation boundary finally legislated in 1975.

8. We kept working on more specific lines to describe our complete-Park proposal. Here is a sketch map I made of an intermediate step:

A significant effort, headed by J. McComb and J. Lobel, was made by the Club's Grand Canyon Chapter to work with the AGPA, B. Winter, and the state Game & Fish Dep't, R. Jantzen. This included field trips and incorporating the personal knowledge of chapter members. These discussions helped the chapter make some specific recommendations over to the western border of the existing Monument, beyond which nobody knew much about and for which there were no good maps available. It could almost go without saying that they were explicit about not including any Navajo or Hualapai land. Here is what the chapter came up with in Dec 1967:

1. From the highway bridge to the National Forest, set the Marble boundary ½ to 1 mile back from the rim; south of that follow the rim. This would avoid encroaching on the buffalo ranch.

2. Leave the boundary as is across the Kaibab; there is too much logging damage, too many roads, too many deer, too many hunters, to consider adding any to the Park.

3. Since hunters do not use the esplanade, the NPS Kanab addition should be enlarged by going up the Canyon farther, following the rim to Jumpup Point, then going west 3 miles & south.

4. Add all the current Monument to the Park, even though the plateau has no unusual scenic values. Do not include any more of Tuweep Valley; there is too much private land.

5. Leave the small piece of Kaibab NF with Mt Trumbull as is.

6. Without mention of the Havasupai, the national forest south of the river and going west from Cataract would be added to the Park.

These were solid recommendations, showing both flexibility and the difficulty of avoiding disagreement if it came down to drawing specific lines on the ground.

For the official, national, Sierra Club position, we finally, flying grandly above realistic considerations, reformulated our complete-Park proposal into the Great (upside-down) Bird. Here is the official Club map from early 1968:

First, we dropped any notion of including Navajo or Hualapai land. Then, using very broad-stroke lines neither on township or natural features, we emphasized additions of Marble on the west, way upstream in Paria, Kanab and Havasu-Cataract (ignoring the Havasupai) Canyons, more of the Kaibab, much of Toroweap, and all the western Canyon on the north side. We went all the way to the Grand Wash Cliffs on both north and south sides. Intermediately, we had looked at the Little Colorado addition, then chose to hope for a Navajo declaration of a tribal park instead. Toroweap and the Grand Wash Cliffs were added during our 1967 deliberations.

This proposal, approved at the 3-4 Feb 1968 Sierra Club Board of Directors meeting, was again a conceptual declaration of a complete Grand Canyon National Park, an attempt to enlarge the debate beyond fixes, dam-stopping, and resource trading.

Maybe this is a little prettier:

LOW-LEVEL CONSIDERATION; NO ACTION

Internal NPS discussions involving the Park, Region, and DC were active from the summer of 1967. This may have been stimulated by Secretary Udall, back from his river trip through the Canyon. He had discovered that people could not get out after Phantom, and to overcome that "serous inhibiting factor to full use", he set up a high powered committee to choose between Diamond Creek or Whitmore Wash for road access to the river. It would be a worthwhile business concesson for the Hualapai. To NPS Director Hartzog, he wrote,"we erred in not recommending that the Marble extension reach all the way to Lees Ferry area" as the logical north boundary, not the highway bridge. [Did he know that the administration and the Case bills did go up to Lees? And this seems to be the time that Saylor revised his Park plan to start at Lees.] Udall thought that since there is little water available in the remote areas, they would be given wilderness status.

An August NPS report pushed the Monument deletions; they might result in "more amicable relations" with B.L.M. A 500' setback along the Marble rim would prevent non-conforming intrusions, and allow for interpretive, administrative, and visitor facilities.

On 1 September 1967, NPS's Service Center (SSC)** reviewed various proposals for DC, though did not grapple with our ideas for a complete Park. They seemed concerned about not offending pro-dammers. An important consideration [one that is a continuing sore point] that arose from proposals like Saylor's & Case's to go downstream came from Lake Mead NRA sup't Richey: Do not take in that Whitmore-Parashant area that is important to local grazing operations. That section (referring to the esplanade cut into by Parashant-Andrus canyons with the Whitmore lava flows) is, they [falsely] averred, "scenically dissociated" from the Canyon. Therefore, it should stay in the NRA; Richey and SSC agreed on that.

The SSC concurred in the Kanab plateau & southern deletions from the Monument: no particular park values, useful for grazing. [Let me comment here: they are taking a situation that was vibrant in the 1930's but had been in steady decline since. The grazing in the Monument & NRA sections of the Canyon, for instance, is long gone.] Also the deletions could be used for land exchange. Having served the ranchers, they stiffed the Havasupai by recommending taking Long Mesa, plus enough more National Forest to control the Hualapai Hilltop trailhead to Supai. They objected to letting the "splendid tract" of north Kaibab forest at Fire Point fall to lumbering operations; it is a fine overlook. SSC adopted the 500' setback along the Marble rim. Marble up to Lees Ferry should be in the Park, not Glen Canyon NRA. And the long-sought Hull Tank addition was no longer necessary according to the Park sup't.

GCNP Sup't Stricklin agreed that all of the Lees Ferry historic district should be in the Park. The lower Kanab addition was of "great importance". He seemed to be pleased about leaving Whitmore-Parashant in the NRA for grazing. [I have to wonder: Had these guys been out to see the area? Had they read the reports from the 1940's & 50's? Of course, at that time, we had not, either.] In the Tillotson spirit, he accepted the deletions, while wanting Long Mesa. He wondered about including the south side downstream, too, but was told that was not realistic; Hualapai never approve giving up control, and the south side is Hualapai. "For that matter", the SSC opined, "so is the river bed itself ". Anyway, only one side was needed to block a dam. By October, after some thought, the sup't decided a 500' setback along Marble was a bad idea, since it would bring pressure for an inappropriate road, and there is little threat of intrusions.

The discussions then seemed to have ended for the duration of the 90th Congress. The main business at the time, of course, was to get the damless water legislation passed. The Sierra Club had endorsed the administration plan, even though it contained the compromise that a to-be-created National Water Commission would study what the highest use of the western Grand Canyon would be. Opposing that plan was the bill pushed by Congressmen Aspinall and Udall that included what was now designated Hualapai dam. Tied to it was Aspinall's proposal (#2 above) that abolished the National Monument and disestablished the western 13 miles of the Park, thus giving the integrity of the National Park System a horrific blow by removing protection for a strictly commercial purpose. We thought such a precedent would demolish the Park System. Aspinall's initiatives had upped the stakes to a new level.

David Brower made our basic position clear in his statement on 4 May 1967 when he testified before the Senate Water and Power Resources Subcommittee, then considering the administration plan:

“We believe that the highest purpose to which the United States can dedicate the Grand Canyon, the whole entity, is to preserve it as it is, for all people, for all time. We believe that the entire Grand Canyon, from Lee's Ferry to Grand Wash Cliffs, should be given Park status within the National Park System.”

We were pleased that the administration had proposed the inclusion of Marble Canyon; the next step would be the downstream extension. Brower then listed all the arguments against the dams, marshaling the testimony & evidence presented in various venues since 1965. He described the traveling exhibits, the books, the film, the Club had prepared, showing the Canyon from the perspective of the river, "a different Grand Canyon from the one we are all used to". Without being explicit, he made clear that the Grand Canyon would not be "The Place No One Knew", as Glen Canyon was labelled after its loss. Smoothly, he noted that the administration plan as presented supported our belief there were feasible alternatives to the dam, but it was not the only one.

Evidence justifying a complete Park had been presented by the administration and conservationists, Brower said, and in this hearing, Paul Martin, for the Arizona Academy of Science, will describe a new collection of evidence of the Canyon's value for geology, archeology, & biology. We agreed with their recommendation for a broad-scale, scientific reconnaissance of the Grand Canyon, which can only be done if it is left as it is. And this can be done if Congress protects it as a National Park.

The next day, as mentioned above, Senator Case introduced his bill for a more complete Park. He emphasized the damage that the dams would do. He cited the latest work making clear that the dams were not necessary for water or power for Arizona's project, but only to create a development fund for importing water into the Colorado Basin. The threat posed to the Canyon by the dams can be extinguished by enlarging the Park. "The highest and best use of the Canyon would be to keep it as it is, undammed, undemeaned and undiminished."

I have one of those physical flash memories of Senator Case speaking on the Senate floor; probably apocryphal, but it is still pleasurable to recall this fine legislator, an original.

Although there was to be no consideration of Park boundary changes in the 90th Congress, there were many topics active on our Grand Canyon agenda. Sep & Oct 1968 Grand Canyon chapter meetings looked at wilderness, rim & trail development, master planning, and river running, all indications, aside from the boundary matter, of the hectic years that lay ahead.

THE REAL ACTION

On 30 Sep 1968, President Johnson signed the Colorado River Basin Project Act. Almost at the very end, it contained this provision:

SEC. 605. Part I of the federal Power Act (41 Stat. 1063; 16 U.S.C. 791a-823) shall not be applicable to the reaches of the main stream of the Colorado River between Hoover Dam and Glen Canyon Dam until and unless otherwise provided by Congress.

That was it. The big victory was a Nothing; there was nothing in the Act that authorized any dams in the Grand Canyon.

One aftershock of this 1960's earthquake came as Johnson left office on 20 Jan 1969: he proclaimed Marble Canyon National Monument (though the Federal Register listed it as Marble "County"). We are indebted to reporter R. Cahn of the "Christian Science Monitor" for a back story. In the summer of 1968, Johnson asked for ideas on actions he could take as his administration closed. Secretary Udall brought up the Antiquities Act, which had not been used for several years since Aspinall took a dim view where there was no emergency. Udall asked conservationists for ideas, and winnowed 17 suggestions down to 7 (including Arches, Capitol Reef, Sonoran Desert) which he presented to Johnson on 11 Dec. The idea was to use the Antiquities Act to protect expansions while asking Congress to act on Park status. Udall cleared the idea with Saylor and Jackson, who approved. However, Aspinall was "out of town", which might mean that Udall did not want to confront him or judged he would oppose the changes no matter what. Johnson went ahead and mentioned the possibility in his January State of the Union, which aroused Aspinall's suspicions that something was going on. When he heard them mentioned at a Senate hearing, he telephoned Udall on 15 Jan to warn of his opposition. While they had the power to proclaim, there would be no appropriations. The additions werent necessary since the lands were already protected. Udall was supposed to brief the incoming Secretary, which he did. Thinking Johnson was committed, Udall then put out a news release, but Johnson felt pre-empted and via a "heated" phone call, told him to call it back. Johnson's staff performed some last minute changes, but although some actions were dropped, Marble Canyon was proclaimed.

Proclamation 3889 started by calling Marble "a northerly continuation" of the Grand Canyon. It had the usual scientific and natural values in its geology and paleontology, worthy of being permanently protected. (Note that the provision of the Basin Act above had already protected Marble against any dam not congressionally authorized.) The Parks Advisory Board had endorsed Marble's preservation in Apr 1967. So the President, under the Antiquities Act, reserved the described federal lands "from all forms of appropriation under the public land laws", setting them apart as Marble Canyon National Monument. Lands that had been within the national forest or game preserve were excluded. Any reservations or withdrawals (namely for water, power, or reclamation) were revoked.

Here is the Sep 1968 map as proposed. It was not used in the proclamation which is all verbal description. I added the green line.

The boundary was more or less a horror. On the west side, where the land had been in the Forest, it was confined to the rim. North of the Forest, it ran 500' back from the rim, except that it cut straight across the side canyons of North, Rider, Soap, Badger, and one unnamed. It only went to the bridge, not to Lees Ferry.

The east boundary was:

the west boundary of the Navajo Reservation;

which was the south bank of the river,

excluding lands withdrawn for power etc.,

which withdrawals were now revoked;

nevertheless, the withdrawals' eastern boundary was the Monument's eastern boundary.

Got that?

Without describing them in detail, the boundaries of the various withdrawals were a hodge-podge of differently described lines, of absolutely no value in setting an administratively feasible line for a Monument. The apparent point was to keep out of Navajo hands, the lands that had been given to them and then taken for a dam. I have discussed this unwarranted action in several posts of July 2010. That discussion, of course, is focussed on the Park boundary, which absorbed Marble Monument in 1975. What makes this action even less sensible is that while the Monument declaration hands administration of the river in Marble to the Park, it leaves out the boat put-in point, administratively the most important. And why was it more deferential to the Forest Service than to the Navajo or B.L.M.?

But that is a different debate. For now, the Johnson-Udall administration was done. The 90th Congress was done. The Colorado Project Act was done.

And the Canyon was safe from any more dams.

============================================

* This is one of several NPS map designations. Most of the Park proposal maps over the next several years were drawn by NPS, usually at some legislator's request. In a separate entry, I will list all I have record of.

**Although I do not know all the details of these internal reorganizations, such functions as master planning and boundary revisions seemed to have started out as individual Park functions (Tillotson & Bryant as Superintendents typify this), then were moved to regional offices (for GCNP, Southwest, where Tillotson moved in the 1940-50's; later on (early 1970's), Pacific, and so on). Then sometime in the 1960's(?), a Service Center (first San Francisco, later Denver took over all this work. The DSC thus figures heavily in 1970's action on boundaries, plans, additions, wilderness, and such. What this meant for the origination of ideas, and delays in approvals, and negotiations, I mostly can only guess. This buracritiization, however, was something that led us Canyon advocates often to indifference, frustration, and even dismissal of NPS as a force to be reckoned with.

Sources: Much of this material comes from the files I maintained at the time, and have kept, along with notes I collected of agency files and archives in the 1970's.

In particular:

Sierra Club Executive Director files, available through Univ. of Calif. Berkeley's Bancroft Library.

NPS Archives, DC & GCNP

Arizona Game and Fish Dept files, 1967-74

Bureau of Reclamation, Boulder City

Forest Service, regional office

No comments:

Post a Comment