The Narrative, May

The story picks up from a low point for us, as we searched around for ways to counter the gains made by the Havasupai forces led by Sparks.

Pontius let me know, 10 May, that Seiberling had talked with Udall and given him our map showing the nearby private land and ranch. Seiberling had argued the Havasupai position was just too much of a giveaway of National Park land. Pontius did worry that a shift in position could lead to Udall and Steiger taking differing positions. To help clarify the issue, Mo had volunteered to fly over the area with McComb and Sparks on the 26th, though the latter had been clear that he was not in favor of considering private land for the Havasupai.

My conversations continued, with a Forest Service official indicating one advantage Sparks had gained: though horrified by the transfer, any Forest Service comment or action was stifled by the new administration position, though he could look for any updated claims by other tribes to Forest Service lands. In checking with a Senate staffer, I found a reluctance to take this on after the troublesome Blue Lake controversy of a few years earlier. The House Interior Committee staff were also "really horrified" by this breakdown in the Indian claims process. However, they knew subcommittee chairman Taylor would be reluctant to get in a big disagreement with Udall. They noted that a list of claims in Parks could be compiled.

Seiberling told me about his talk with Udall. He had objected to the Park losing the Great Thumb Mesa in particular, even with the protections Udall promised. It was just a bad precedent.

Maybe because Tucson was a center of Udall support in Arizona, there was an active pro and con exchange with the congressman and in the newspapers. The Havasupai got involved in the exchanges. Many clever, but late, suggestions were made. There was no diminution in the determination of those who were pro-Park and anti-transfer. This might have seemed to be a compromisable matter, but once the central question was whether title should be transferred or stay in the United States, the split was unbridgeable.

On 14 May, Pontius let me know that the Havasupai lobbyists believed they had the Republicans "all sewed up" for the transfer. Also, a hunter was to be included on the plane trip, apparently at the instigation of Goldwater's aide, Emerson. This was another marker that a little bit gratuitously, but hardly coincidentally, "Goldwater" & staff had now re-joined the effort that they had run away from in 1973. Goldwater inserted a vicious attack on the Sierra Club in the 20 May Congressional Record, S8523-6: He started with the club's "ingrown antagonism" to Havasupai "survival". "At odds with much of its membership", national officers "remain adamant". The club's "intense" opposition would "banish this diminishing tribe" to "isolation in the bowels" of the Canyon. The club is using its "full powers" to prevent the Havasupai from owning their one trail of access. "Professional conservationists" care more for "rock and sagebrush", but the Havasupai feel more for this land "than the Sunday hiker or professional environmentalist ever can". He could not understand the club's "persistent and unmovable resistance", "the vast ignorance and fundamental lack of understanding"; it is "a closed society", a "self-centered, selfish group" with ideas "which fit only their personal conceptions". It is only "the national level" officials that have not "caught up", but can be seen as "regular visitors to … closed congressional policymaking meetings and … remain prisoners of their own self-centered world". "Dead set in their own assurance", they insist the Havasupai accept unwanted lands "to which the Sierra Club would intern them". They "would play a cruel hoax" and perpetuate "a terrible system under which the Indians now lose all their children". "Perhaps we might just pause as we go hell-bent to preserve the bighorn sheep … and think about preserving some endangered people". Last year, the club's "massive, nationwide campaign of opposition" pressured the Senate committee" to change my proposal, and then led to House subcommittee action "that would completely gut the aspirations", a plan "identical" to a club plan presented at my home. If the club has its way, "there will be no Havasupai; they will disappear--so that the Sierra Club can brag that is has won another power play". "We must not allow that to happen."

[I quote this example of Goldwater's vaunted integrity and truth-telliing at length, with its language and vigor typical of the public controversy, because it is such a contrast to the on-going working relationships in the House that brought the legislation through to final passage. It is also a useful marker in explaining Goldwater's future actions.]

"Conservation Report", (published by the National Wildlife Federation, home base of pro-hunter groups but with much wider conservation interests, the "Report" tried to be concise and comprehensive on political & governmental matters), 23 May, called the legislation a "hot potato", and said the "precedent-setting grant of national park and forest lands to an Indian Tribe" was the "prime" issue. Describing Steiger's goal of offering an amendment to allow a 400' dam, Goldwater was said to doubt its chances, although Emerson said Goldwater "would not oppose its addition". Both Nixon's and Udall's Havasupai proposals were described, the author saying no boundaries had been set. Half the article was devoted to the general difficulties that would follow a grant to the Havasupai.

On the 26th, Udall piloted the overflight with McComb, Sparks, and a hunter, Thompson. They flew north over the huge Boquillas spread, then over the Havasupai-desired lands in the Forest and Park areas, and over Supai itself. McComb and Sparks fought over everything, the former told me, while Udall was silent. The quality of the land, whether economic or Park-worthy, was laid out below them, including the relationship between plateau, rim, and gorges. McComb followed up with a map that the Havasupai had produced in 1971, that he told Udall showed that they had "more interest in acquiring the Boquillas lands" at that time. The map also showed a 1/8th-mile setback from the rim, and did not include all the Great Thumb. Little effect was registered.

Sparks consulted with Udall on the 30th, and the next day, Pontius told McComb that Udall would probably push the boundary over the rim. A new plan would be drawn up to discuss with Steiger next week. "All bad news", I recorded, in line with hearing that the committee had received a "bushel" of "overwhelmingly" pro-Havasupai mail. A 30 May article from the Am. Indian Press Assoc. on the Nixon and Kennedy endorsements of the transfer listed backers including the AFL-CIO, League of Women Voters, ACLU (Arizona), & the National Council of Churches. McComb & I were named as "clearly taking the lead in opposition". NPS was said to be trying to "sabotage the President's position", and "at least one NPS female employee" had been around Capitol Hill.

The Havasupai newsletter, 29 May, summarized their view of the previous three months: After the subcommittee mark-up, the Havasupai had hired Joe Sparks, of Scottsdale, a "brilliant lawyer" at the same time that the executive director of the Assoc. on Am. Indian Affairs came to Supai. This was before 20 March, when six Havasupai and Hirst were sent to work with Sparks in DC. They lobbied for three weeks and came home, though two returned for a second round. All this activity had changed the whole picture. Groups in support (in addition to the above): Quakers, Am. Anthrop. Assoc., AAUniversity Women, NEA, and three Sierra Club sub-groups. We now have an "extremely good" pamphlet from the AIAA.

Sample Ammunition

During June, as throughout this run-up to House Interior Committee action at the end of July, various pieces--position papers, defenses, attacks--were produced. I am going to pick and choose among these items, not always dated, to provide a sense of the content of the arguments. The narrative, June on, will pick up below.

An echo of the attempt to undermine the Club position showed up in a Durango newspaper report on a Club regional committee meeting. Frank Tikalsky, a Havasupai supporter, had been named to head a study group to make a report for the Club Board, He had had the support of Robert Euler, expert on the Hualapai and Havasupai. Euler stressed the need for "a healthy cattle industry". McComb spoke at the discussion, but those present chose not to support the Club's pro-Park position, reaffirmed in early May. Still, questions were raised about the dissent during congressional office visits. So in early June, the Club's Executive Director wrote to all Committee members, asking that any land transfer be rejected. Instead the Club urged that a Havasupai land base 1) not include high Park quality lands; 2) be made up of contiguous ranch lands that offer better grazing; 3) include traditional use of certain park lands; 4) be improved using park and forest funds. The two legitimate national interests of Grand Canyon protection and enhancing Havasupai well-being are in conflict only because the park lands are "free". Yet there are the costs that the benefit to the Havasupai would be questionable and other such requests would be encouraged. The recent change in the President's position would require an environmental statement, and it could lay the foundation for a long-lasting solution.

Also included in this letter was a plea to reject any amendment that would facilitate dam construction.

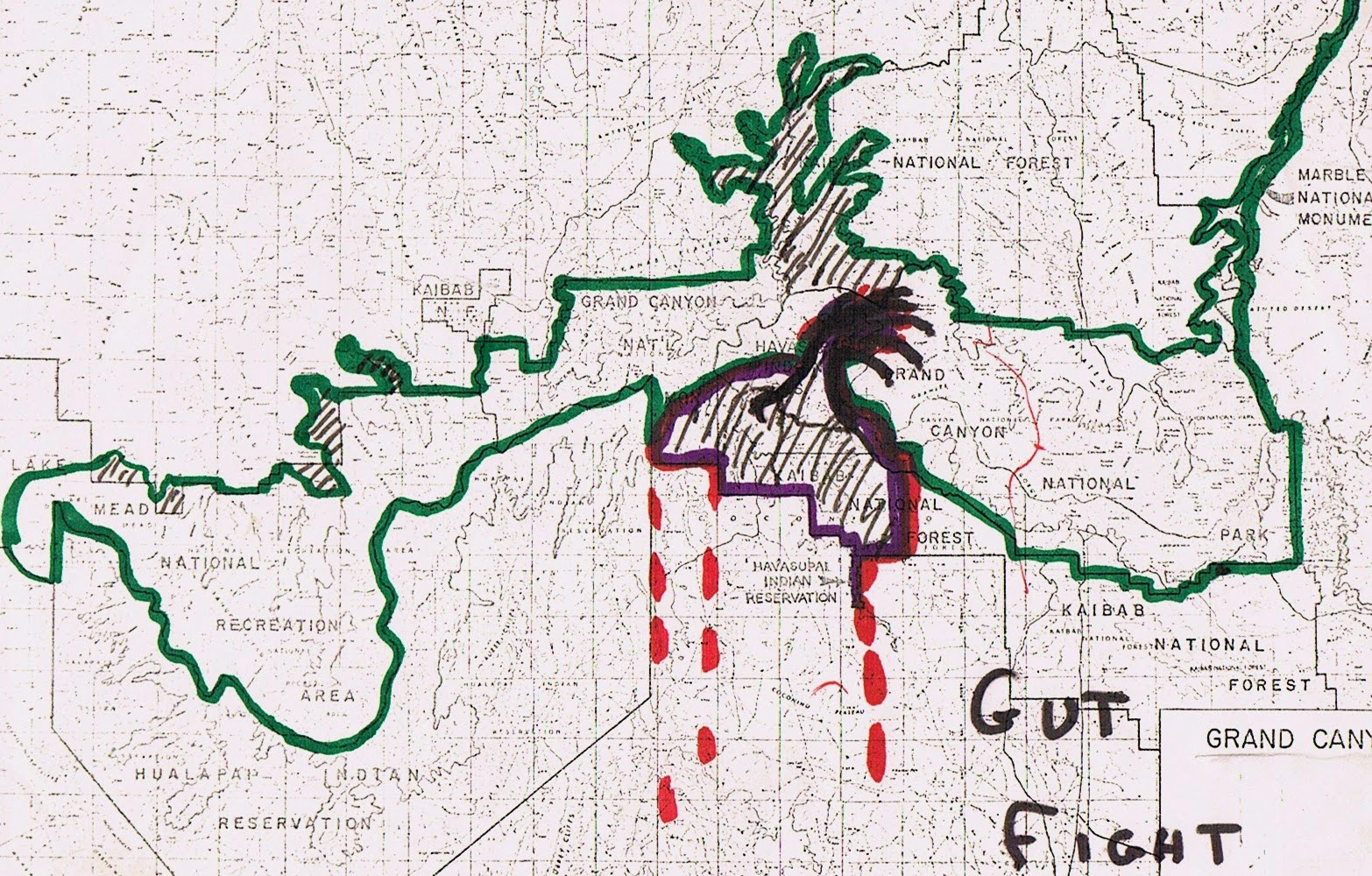

Later, during his lobbying visits, McComb used a fact sheet making the above points, along with acreages and this map:

The clear purpose here was to show how much of the requested land was really inside of, part of, the Grand Canyon, and what good could such a place be for the Havasupai? Why did the Havasupai need to go almost all the way to the river?

The language accompanying the map directed that the Secretary of the Interior approve a land use plan for the protection of the area's values while allowing traditional uses like farming, grazing, and religion. The Secretary would carry out conservation measures on the land.

The private ranch land proposed for the Havasupai land base by the Sierra Club, though not marked here, extended down through the area where the letters "C O C O" "PLEATE" show up. The Club position called for 303 kac, of which 200 kac were private and state, 77 kac were forest, and 23 kac were from the Park. There was no mention of any plan or environmental & park values.

Another "Dear Colleague" letter dealt with the "tangle of individual Indian suits & claims" that Congress would be "plunged" into dealing with. An accompanying memorandum argued that Congress could, and through the Indian Claims Commission, did "extinguish Indian title". This memo brought out Joe Sparks' fiery rhetoric; the Havasupai fervently believed their title was valid and unassailable. [Incidentally, in 1990, the question of extinguishment, now affected by PL 93-620 came up in a court case when the Havasupai (and others) tried to stop the opening of a uranium mine nearby.]

Martin Litton, a champion for the Canyon on many issues, wrote three pages on 12 Jun to the L.A. Times attacking its "distorted" editorial of the 9th. He blamed its publication on Senator Kennedy, whose information came from persons with "questionable" motives. Using the map above (as pushed by Sparks), Litton set forth a panel of horrors that would beset cherished Canyon places. He attacked the Havasupai and defended the Park Service, often with extensive detail. The Havasupai's lives in their "Shangri-La" were "not nearly as harsh as those endured by many other Indians". "Unreasoning, senseless outcry over Indian 'rights'" was driving congressmen to "cave in". He asked the newspaper to contact the Canyon's allies, get the facts, and publish "both sides".

Three more pages, probably from the Forest Service, were circulated showing land claims that could affect forests, parks, etc. The Park Service had its own list of "Unresolved Indian Rights". Following this line, a column in the Arizona Republic 22 Jun presented details of many nearby claims. The Interior Solicitor, with no need to choose a side, considered three situations, concluding that legislative action on the Havasupai claim would not preclude a "variety of positions" on other such cases.

When telling the story of a highly emotional struggle, at a 40-year remove, it is too likely (and just as well) that the emotions have quieted, that a dispassionate view is attainable. At times, writings from the fight do convey the extreme feelings, though more often the problem of keeping the attention of important figures who are not so wrought up leads to a seemingly balanced presentation. And these presentations very often need to be brief--one, two pages at most. in my file there are several short pieces attacking the Havasupai proposed transfer that were as "vigorous" as I could make them, accompanied by the following cartoon I drew, in which the expanded Park, outlined in green, is being attacked viciously from below by the claws of the Havasupai land grab. Blood flows.

The Narrative, June

During the first days of June, looking at what I had learned, I came to the conclusion that a trip to Washington would do no good without an effort to get mail to committee members. McComb did not agree with my evaluation -- which led to some coolness -- thinking it was essential for us to have a Washington presence. However, I had a higher purpose in mind -- to spend two weeks with my daughters traveling and camping through and among the wonders of southern Utah, arriving back in Tucson on 17 June.

Whatever my opinion, June was no quiet or cool time. Transfer opponents kept on producing various ideas and arguments, trying to cause doubt about the validity of the Havasupai case. Pro and con missives proliferated. The 31 May "Conservation Report" called the dam idea "the most controversial", and claimed conservationists wanted new hearings on it and the Havasuapai transfer, saying the issues were not fully aired in the November hearing. [True enough, there was little debate, but there was testimony on both issues. What can be read between the lines here is that the hunter groups had been asleep at the switch during that vital period of November 1973 - March 1974.] In discussing the transfer, the author said "public access" and "existing grazing allotments on which the present permittees are dependent" both "would be eliminated". Concluding with a reminder of the bitter battle over Taos Blue Lake a few years before, the "Report" quoted statements made then about no precedent being set.

It could not have helped our morale that there were more pro-transfer editorials, e.g. in the "Christian Science Monitor". Likewise, it was tough to receive a letter from strong conservationist Senator Nelson of Wisconsin, who sent the Club DC Representative a help-the-Havasupai plea. The latter, Brock Evans, was not deterred; a strong opponent of the transfer, he had already been in to argue with Udall's staff.

The heavy pressures building for the Havasupai in this period stirred up those with anti-transfer opinions to stiffen their arguments. About 20 Jun, there was a meeting to go over the land transfer between Parks Subcommittee chair Roy Taylor, his staffer Lee McIlvane, Udall, and Pontius. Taylor put forth his view of the problems the transfer could pose, though he had not settled on pro or con yet. While we do not know the details of his objections, the result was that Udall again recalibrated his position in its details. (My post of 13 Dec 2013, dealing with the numerous drafts of the Havasupai provision, might show this, but is frustrated because of the lack of dating.) Consequently, during the period of June 18-28, in my phone conversations from Tucson with Pontius and McIlvane about what was being considered, I was gradually getting a sense that change of some kind might come, more in our favor. This sense took real shape on 27 Jun when Pontius told me Udall had decided to work with Taylor, to satisfy his concerns. Pontius added he had just told Sparks of this shift, angering him. It would be fun to believe that a conversation that Udall had had the day before with the colorful, often bombastic, anti-Havasupai Martin Litton contributed.

At this point, when McComb returned to DC June 21-8 after attending a club staff meeting [no doubt a morale strengthener], he evaluated Udall's situation as being that the "Indian guilt trip" had gone too far, a point Litton made at length in his letter to the L.A.Times. Udall allowed to McComb that he was irritated that there was so much more mail on the Grand Canyon issue compared to his then chief project, land use planning. There were 3" of mail, now running about 50-50. Thinking of his 1976 presidential ambitions, Udall averred that if he had to run against Ted Kennedy, he might as well fight him on this--he had heard that Kennedy was pressing House committee members, e.g. Roncalio, Martin. (Also, Senator H. Humphrey re-stated his support of the Havasupai; he too was a bill co-sponsor.) Udall did feel obligated to stick with the 250 kac figure, but 95 kac of that would now stay in the Park, yet available to the Havasupai for traditional uses. Also, Steiger had called him, asking for a delay beyond the 10th; he said he was OK with a setback of ¼-mile from the plateau rim. Steiger's real concern showed up in his revised dam amendment that a license be directly issued to the APA, no more delay. He did not seem to object to Udall's Park addition of the lower part of the Colorado, nor extending the park upstream to the Paria, though he had no love for the two-year wilderness study.

The pro-hunter "Conservation Report" of 28 Jun only attacked the Havasupai transfer, echoed by the AWF (Arizona hunter group) voting unanimously against it; apparently they still were not in on the "secret" additions that were beginning to upset the state Game & Fish Dep't (see below). A San Diego newspaper also focussed on the Havasupai, and the dam issue, as it concluded, accurately, "So another storm threatens Grand Canyon, which has managed to remain a political hot potato through most of the years of its existence as a park."

Further negotiations; New provisions

McComb now went about visiting half of the Committee members. McIlvane, staunch against the transfer, advised him that he would work to minimize the land transferred in trust, while putting restrictions in place that were so severe no tribe would want to try it again.This resulted in a "confidential" memo, "MORE HAVASUPAI LANGUAGE", that Pontius provided us on 2 Jul. McIlvane and Pontius settled on the final proposal 5 Jul. McIlvane opined Taylor was against the transfer on 8 Jul, and presented his ideas to Taylor 9 Jul.

What the drafters had come up with used the foundations I wrote about in my 12 Dec 2013 post; they laid them out in seven provisos of section 10(b), which I will summarize and, not to jump ahead, show what was changed before the actual committee discussion.

1. The lands must be used only for traditional purposes. This must have been too restrictive because the committee version changed it to "may" be used.

2. Agriculture & grazing were "exclusively" uses by the Havasupai. Later, "exclusively" was dropped.

3. Burial ground use may continue.

4. There would be a secretarial study for a land use plan, done in consultation with the Havasupai. First, the secretary was to "develop" a plan; this was changed to "develop and implement" a plan. The draft said there was to be "one compact and contiguous" area for residential, educational, and other community purposes. The change was to a "selection of areas".

5. No timber use (except by tribe) and no mining. The exception was deleted.

6. Non-Havasupai had access to visit park lands in locations established by the Secretary. The change added consultation with the Tribal Council. In any case, if the Havasupai consented, non-Havasupai could use the land temporarily for recreation. [This was double-edged; on the one hand, non-Havasupai would have recreational access, but on the other, it could only be temporary, the implication being that no permanent structures could be built to provide for visitors.]

7. Except for 1-6, the land "shall remain forever wild" and no uses shall "detract from the existing scenic and natural values". In the draft, the Secretary decided what would detract; this was changed to what the land use plan would say.

Section 10c put the Secretary in charge of land conservation. Language allowed the Havasupai access to public lands, other than the enlarged reservation, for sacred or burial places. The later version added they could go on public lands other than their Reservation to seek native foods, paints, materials & medicines.

What this language sought was limitation by listing what was allowed, rather than

protection by listing forbidden uses, such as tramways, excessive roads, waterworks, etc. There is an implicit respect that what the Havasupai said they wanted (land back for traditional uses & grazing) circumscribed what they would do. Did we have to fear that these provisions were not strong enough to preclude industrial-tourist development? Could we be reassured that reducing the size of the transfer and pulling it back from the rim would be enough to bar "detraction of existing scenic and natural values"? Udall thought so, and although the question of whether there should be a transfer at all would be fought down to the last day, his positive outlook would carry more weight than any catalog of potential horrors that we could cook up. On the other hand, our opposition insured that the matter of what could be done was heavily aired.

McComb heard that the two non-Havasupai Havasupai lobbyists, Sparks & Barron, were visiting every office every week; he wondered who was putting up the bucks. (But, then…?) Of course, after hearing about Taylor's refined position, the two again contacted all committee members, while Sparks (a Republican) went to the Speaker (an Oklahoma Democrat) when he heard about Udall's shift--did Sparks have a contact there as well as in the White House? Guess not; it turned out to be a rumor. Surely their appeals would have been self-limited--what Udall/Taylor had worked out was based on what the Havasupai had already said they wanted.

At this point, the last few weeks before Committee action, I will break in order to present a treatment of the efforts being made by the "newly awakened" hunter lobby in Arizona. Eventually, this would lead to a triangular situation: the Havasupai pushing for their land transfer, with us pushing back; the hunters pushing against our Park additions and, a little, against the Havasupai.

Sources: Again, the principal source is my journal and the piles of papers I collected that summer.

No comments:

Post a Comment