The story of Marble Canyon National Monument is a facet of one aspect of the mid-1960’s conflict over whether to build dam(s) in the Grand Canyon. (Pieces of this story are in other blog entries, e.g. Dams, The Navajo Boundary, but the material in the Stewart Udall archives makes it worthwhile to bring the pieces together.)

That aspect was the effort by the Arizona Power Authority (APA) to gain a license to build and operate a state, as opposed to a federal, hydroelectric dam in the reach of the Grand Canyon upstream from the northern boundary of the National Park. The federal plans were on hold through the 1950’s until 1964 due to a legal contest between Arizona and California over Colorado River water rights. This contest included a hold on federal Reclamation development in Arizona involving the dams and the Central Arizona and other projects. Some Arizona politicians, disgusted at this delay in federal activity, decided to bring about River development using state agencies, notably by the APA pursuing a state-funded dam in Marble.

(Side note. Marble Canyon is an ambiguous term for the section of the Grand Canyon dominated by the Redwall Limestone (J.W. Powell thought it marble-like) upstream of Nankoweap Creek. The Marble section is an integral part of, the introduction to, of the Grand Canyon. In the dam controversy, dam backers often tried to fuzz up this integrity, while defenders of the Grand Canyon would use the term “Marble Gorge” to emphasize it.

“The dam” refers to three concepts in the post World War 2 period: a dam to back up the Colorado that would then be diverted, by-passing the Park, into a tunnel to Kanab Creek and through a very large power plant; a federal hydropower dam that would produce power and allow the river to flow through the Park; a state hydropower dam at a site down-river from the federal location.)

The APA effort to gain a license for its hydropower dam took place before the Federal Power Commission, which controlled such non-federal applications. The effort, in spite of opposition from Los Angeles, the Navajo, the feds, and Canyon defenders, was so likely on the verge of success that another set of Arizona politicians, led by Senator Carl Hayden and Interior Secretary Stewart Udall, pushed a successful effort in Congress to pass a moratorium from 1964 to 1968 on the FPC’s power to grant a license, thus suspending the state effort.

That was exactly the period when the legal controversy was resolved, and the federal government, led by Secretary Udall, proposed a huge Pacific Southwest Water Plan that included a federal hydropower dam in Marble. Legislation to effectuate such a plan was battled over in the 1965-6 Congress, with the result that the effort failed before it reached a vote in the House of Representatives.

In late 1966, Secretary Udall launched a new initiative. More modest, it eliminated all of the proposed dams in the Grand Canyon. This plan was introduced in the Senate by Hayden and his allies, and passed. In the House, the situation was more complicated, as the dams still had support. The end result was that in 1968, a dam-less Colorado River Basin Project law was enacted, which included a permanent bar on any but a congressionally-authorized dam in the Grand Canyon. In effect, this ended the Grand Canyon dams controversy.

In my blog entry of 27 Apr 2012, “A Complete Park: II. Competing Visions 1967-8”, I listed the several bills that aimed to extend the Grand Canyon National Park. (That entry can be found under the tab for “Parks”.) A major goal was to eliminate any more controversy over Grand Canyon dams. They all included some portion of Marble Canyon, varying on the length protected and whether Navajo land on the east side would be taken in along with the west, federal, side.

From that blog entry:

Determined not to antagonize the Navajo in drawing up legislation, in February 1967 NPS Director Hartzog directed local NPS officials to talk with Navajo leaders about GCNP expansion. A meeting with the Navajo Natural Resource Director to discuss Saylor's inclusion of the east side of Marble and the Little Colorado brought a resounding NO. Interior had their draft, with no Navajo land, to Congress by 9 March. Interior-NPS strategy was not to stir up Navajo antagonism, but to work toward long-range establishment of ties. An NPS fly-over of Marble confirmed the feeling that Marble was a striking feature that should be protected for river running, but maybe Park status was not needed for the entire reach or for the east side. Of all the new proposals, the administration bill was alone in limiting itself to Marble's west side.

On 13 March 1967, this bill was introduced as S. 1300 by Interior Committee Chairman Jackson of Washington, no doubt by request. It added Marble Canyon up to Lees Ferry, but only land on the west, federal, side. The Secretary’s Parks Advisory Board supported this addition in April.

There was no action on the Park proposals as the water project bills went through Congress, culminating on 30 Sep 1968 with President Johnson signing the Colorado River Basin Project Act. Almost at the very end, it contained this provision:

SEC. 605. Part I of the federal Power Act (41 Stat. 1063; 16 U.S.C. 791a-823) shall not be applicable to the reaches of the main stream of the Colorado River between Hoover Dam and Glen Canyon Dam until and unless otherwise provided by Congress.

Since there seemed to be consensus that Grand Canyon National Park would be enlarged, and Marble Canyon included, this phase of its story could have logically ended at this point, with it protected and awaiting an inclusive Park bill. However, as the River Basin bill was being wound up, and the Johnson administration was drawing to a close, Secretary Udall asked the Park Service to gather ideas for places that could be proclaimed as Monuments under the Antiquities Act.

Udall’s archived folders on this matter open in a startling way, a handwritten note to the Johnsons with a “painfully sorry” about the last two days of office being “in discord and disarray”, and wanting to wipe them away, leaving the 5+ “warm, rich, unforgettable years” of remarkable collaboration. And remarkable indeed is the lead document, 11 handwritten pages on the “entire” transaction, written 5 Feb 1969, only a couple of weeks after the event. It is a good story, though Marble Canyon National Monument doesnt figure much except as a survivor of the “disarray”.

Udall had been “nursing” the idea of using the Antiquities Act since Johnson had announced 31 March he was not running again. There had been only five proclamations since FDR. A heavy factor was the opposition by long-time crusty opponent of wilderness and other conservation ideas, Representative W. Aspinall of Colorado. He would vigorously denounce anything that tried to avoid congressional action, the whole point of Antiquities Act actions. To keep in good favor with Aspinall, back in 1961 new-Secretary Udall had sent Aspinall a memo that he would try to advise him ahead of time, though there might be exceptional cases.

Udall handed Johnson a memo on the idea of new Monuments on 26 Jul: use of executive power to “preserve unique lands”. There would be issues with Congress, but “adriot maneuvering will help avoid” opposition. LBJ reacted well, even with a small show of enthusiasm, to the idea of “quietly” preparing proposals. So Udall “turned NPS Director Hartzog loose” to prepare proposals. There were informal discussions September through November, when “we” (NPS & Udall) made decisions on what to recommend.

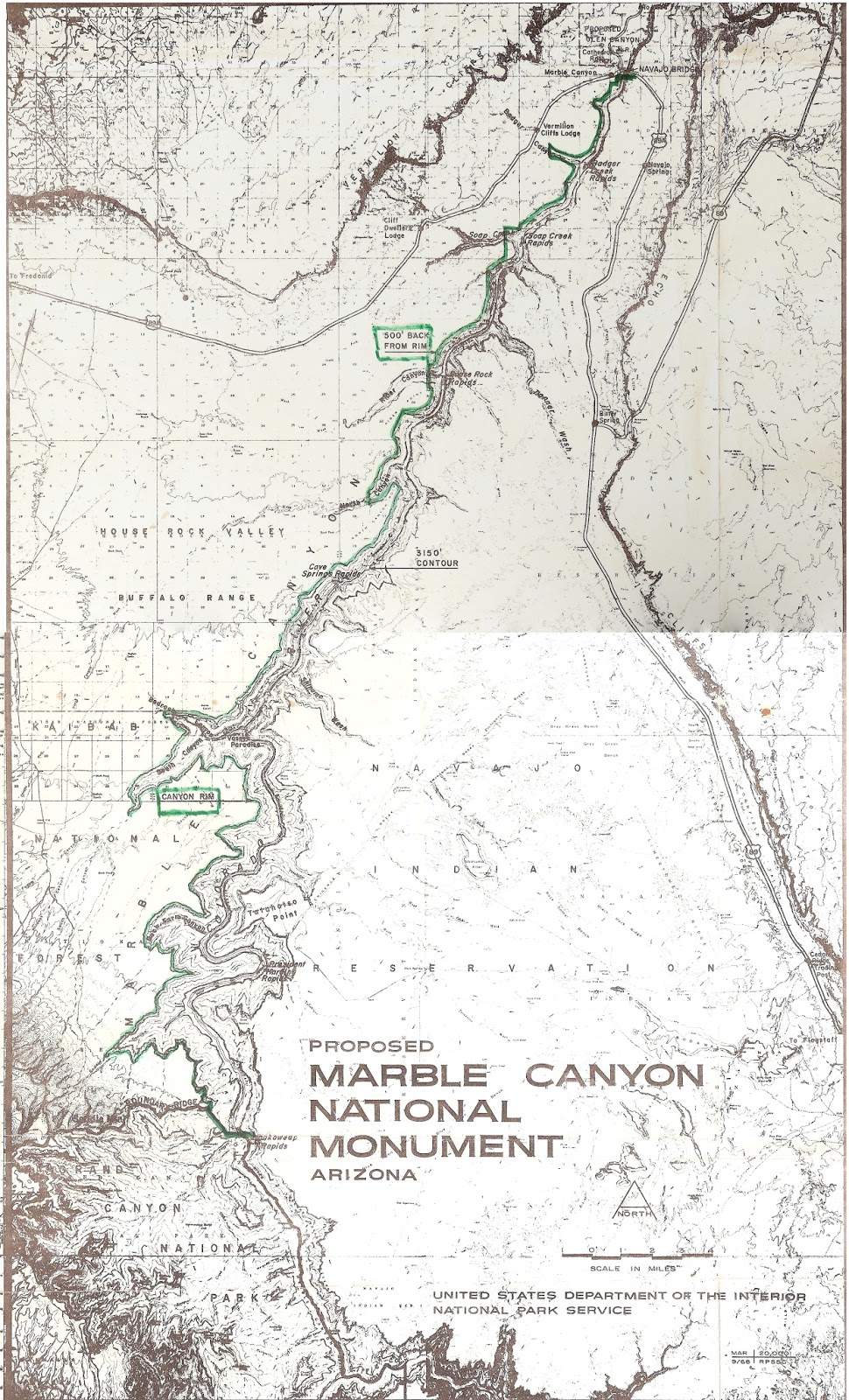

Specifically on Marble, it was one of 19 summaries dated 16 Sep. Also included was the lower Kanab addition, though it was dropped. For Marble, at 26,760 acres, 1000 acres had been added to the 1967 bill proposal with the idea of adding a narrow strip “lying between the River and the Navajo boundary”. At 50 miles long, 20 acres x 43560 sq ft / 5280 ft gives a strip 165 ft wide. But a 12 Nov summary shows a reduction down to 26,080 ac. Perhaps there was further discussion at the Park Service level (those papers are not included in Udall’s archives, but in NPS’), which led to the ambiguous boundary in the proclamation (see below at end).

The verbal description was of a deep, narrow gorge forming the northern “extension” of the Grand Canyon. The western boundary would be the rim, and if Forest Service agreed, some land for overlooks. The eastern boundary “would be the 3150 ft contour on the east side of the Colorado River. This is the boundary of the Navajo Reservation as prescribed by the Act of June 14, 1934.” (But did it average out at 165’? And that description is only partially accurate.) There were “superlative scenic & scientific values”. Marble was no longer essential for a “water control project”, and this status would prevent it from any “despoiling” in the future by such as Los Angeles or “private” projects. On the east side, if there were legislation, and if the Navajo approved, the boundary should be on the rim or beyond. (Note that the Monument only went downstream to Nankoweap, not down to the confluence with the Little Colorado.)

In Udall’s account, the Sierra Club showed up in October “with their expansive proposals”, so “I sent them to Sam Hughes in Budget”. (I remember being in the group that trekked over to the old Executive Office Building — to no avail.) Club President Wayburn wrote 16 Oct, generally approving, but wanted Oregon Dunes, Great Basin, North Cascades, Mineral King, Hells Canyon, west slope of Tetons, added. Mineral w/drawals at least would help. And his p.s: Add Escalante to Capitol Reef and Dark Canyon to Natural Bridges.

Final decisions were made with the Park Service in November. Then the drama started. Udall presented his proposal to Johnson on 5 Dec in the Cabinet Room with five staff, including Clark Clifford, then Defense Secretary, and a VIP to LBJ. Mrs Johnson came in. The hook: a big, positive public event with LBJ as the presenter, invited stars from conservation, a signing, a press conference. Udall suggested calling it a “Christmas present” for the American people.

Udall pointing; Johnson pondering:

Going for big ones in Alaska; Udall at left; Johnson right

The big areas were in Alaska — Brooks Range and south of Denali, totalling 5.6 million acres. There were large additions to Arches and Capitol Reef. Sonoran Desert was the 3rd in size. Marble was the smallest proposed. Udall and his staff felt good about the event. So he wanted to get it done, fearing interference. Instead, weeks went by, what felt to him like stalling. Worse, Udall wrote, other matters pressed, snarling up the Monument move in politics and grievance: a couple of oil disputes, one involving Hawaii, the other Venezuela; a possible stiffing of LBJ over memorializing Bobby Kennedy; Aspinall not really on board, hearing second hand and calling LBJ; the very size of the two areas in Alaska; the possibilty that Clifford opposed and the staffer was dragging his feet; even Udall’s supposedly quiet doubts about Vietnam.

Johnson got the flu, and then wanted to wait until Congress convened. He asked for, and got, memos on what other Presidents had done in early January. Then the staffer began to mix in oil decisions, and Udall saw this as LBJ playing poker with him — I would have to show my hand on the oil decisions, before he would act on the monuments. Then, in the last week before 20 Jan, supposedly Udall was cleared to release news on a couple of days before the end of the administration. But, horror, Aspinall heard indirectly, and called LBJ to object. The final weekend, all was confusion and error; LBJ made excuses to avoid seeing Udall; Udall made the announcement anyway, and then after an angry call from LBJ, had to retract it. Finally, almost petulantly, the President signed proclamations only for the smallest areas, including Marble Canyon. Udall’s summing up: “President had already decided. Silence from Sat p.m. to Monday morning just confirmed his deep anger and his determination to punish me.”

[Politics, the wise know, is people.]

THE THING ITSELF (Map and document below)

Proclamation 3889 starts by calling Marble "a northerly continuation" of the Grand Canyon. It had the usual scientific and natural values in its geology and paleontology, worthy of being permanently protected. (Note that the provision of the Basin Act above had already protected Marble against any dam not congressionally authorized. Also, there was no mention of river boating, and no sense that adequate protection did require including the east side.) The Parks Advisory Board had endorsed Marble's preservation in Apr 1967. So the President, under the Antiquities Act, reserved the described federal lands "from all forms of appropriation under the public land laws", setting them apart as Marble Canyon National Monument. Lands that had been within the national forest or game preserve were excluded. Any reservations or withdrawals (namely for water, power, or reclamation) were revoked. (Did that affect the east side boundary?)

The boundary was more or less a horror. On the west side, where the land had been in the Forest, it was confined to the rim. North of the Forest, it ran 500' back from the rim, except that it cut straight across the side canyons of North, Rider, Soap, Badger, and one unnamed. It only went to the bridge, not to Lees Ferry.

The east boundary was:

the west boundary of the Navajo Reservation;

which was the south bank of the river,

excluding lands withdrawn for power etc.,

which withdrawals were now revoked;

nevertheless, the withdrawals' eastern boundary was the Monument's eastern boundary.

Ok?

Without describing them in detail, the boundaries of the various water-power withdrawals were a hodge-podge of differently described lines, of absolutely no value in setting an administratively feasible line for a Monument. The apparent point in 1934 was to keep out of Navajo hands, the lands that had been given to them, when needed for a dam. I have discussed this unwarranted action in several posts of July 2010. That discussion, of course, is focussed on the Park boundary, which absorbed Marble Monument in 1975. What makes this Monument action even less sensible is that while the Monument declaration hands administration of the river in Marble to the Park, it leaves out the boat put-in point, administratively the most important. And why was it more deferential to the Forest Service than to the Navajo or B.L.M.?

Here is the Sep 1968 map as proposed, followed by the Proclamation, which is all verbal description. I added the green line and the doodles.

================

Sources: My blog on dam history, Park enlargement proposals.

Papers of Stewart L. Udall, in Special Collections, University of Arizona, 473, Box 182, folders 1-3, including several newspaper articles

No comments:

Post a Comment